Vasily Smylsov was born March 24, 1921 in Moscow and learned to play chess from his father at the age of 6. His father was a good player. That and his father’s library created the foundation of this contender. He was a tenor opera singer. Had it not been for his narrowly failing an audition for the Bolshoi Opera in 1950, he might never had made it to Zurich 1953. He once said, “ I have always lived between chess and music”. He once sang operatic extracts on Swiss radio and during the interval of a serious chess game against Botvinnik he sang to an audience of thousands.

Vasily Smylsov was born March 24, 1921 in Moscow and learned to play chess from his father at the age of 6. His father was a good player. That and his father’s library created the foundation of this contender. He was a tenor opera singer. Had it not been for his narrowly failing an audition for the Bolshoi Opera in 1950, he might never had made it to Zurich 1953. He once said, “ I have always lived between chess and music”. He once sang operatic extracts on Swiss radio and during the interval of a serious chess game against Botvinnik he sang to an audience of thousands.In 1938, at 17, he showed some promise as he won the USSR Junior Championship and tied for 1st and 2nd place in the Moscow city Championship. During WWII, international tournaments were very limited. He placed 3rd in the 1940 USSR Championship ahead of Botvinnik. . He won the 1942 Moscow Championship and finished strong in several other regional events.

Despite hitting a post war slump between the period of 1945 -46 with up and comers like Bronstein, Keres and Botvinnik at his heels, his earlier results earned him a place in the Howard Staunton memorial in August of 1946. He finished in third place. For the next couple of years, his results showed a consistent pattern of high finishes against strong company, but with virtually no tournament championships. Smyslov had never actually won an adult tournament other than the Moscow City Championship, before he played in the 1948 World Championship Tournament.

How did he get to Zurch?

Smyslov was one of the five players selected to compete for the 1948 World Chess Championship tournament to determine who should succeed the late Alexander Alekhine as champion. His selection was questioned in some quarters, but this criticism was amply rebutted when he finished second behind Mikhail Botvinnik, with a score of 11/20.

Finishing second seeded him in the 1950 Budapest Candidates Tournament but finished behind Bronstein and Boleslavsky. FIDE granted him the International Grandmaster title in 1950 on its inaugural list.

The third place finish in 1950 seeded him into the 1953 Candidates match in Zurich. To recap, he was a pretty good player back in a day under local competition, showed that he could fight like the big guns in international play though not quite a first place finish, could make the opera, and was a freshly minted GM in 1950 seeded into both cycles of candidates matches.

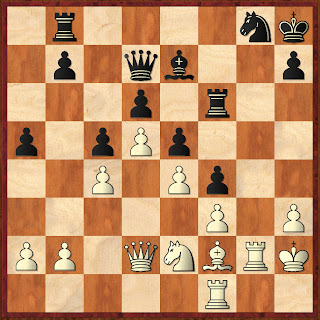

Enter Zurich 1953. After his win against Euwe in round 3, he takes an early lead in the match. This game was a pendulum swinging back and forth. Smyslov played the black side of a Grunfeld and forced Euwe into an IQP dynamic. Euwe had a lot of theoretical preparation for the line and moves ahead with marching the d-pawn. Euwe follows up with an exchange sacrifice that gives him a couple of passed pawns, one being very advanced. Smyslov finds the move that underscores the very weakness of the advanced pawn on d6. In a resourceful maneuver, Euwe attempts a decoy to draw the rook away. Finally, Smyslov accurate play leaves Euwe with a slight inaccuracy that allows Black to come hammering down on the material. He defeats Euwe in both occurrences in this match ( again in round 18). This was the confidence builder he needed. In contrast to the Howard Staunton Memorial where he finished behind the former World Champion, this was the boost he needed.

By round 8, the American was taking the lead. The expectation in round 10 was to see a huge battle. Instead, both players were more into reconnaissance of the other players and saving their major battle for the second have. Indeed, by round 25, Smyslov was leading by ½ a point. Reshevsky needed the win. Smyslov had White and opens with the Reti, which REshevsky had a prepared line that pitched his knights against the Bishop pair. The middle game was a heated dance with neither side conceding to a draw. Then , on move 33, Smyslov plays Rc2 because it prepares a battery on the long diagonal and opens the position up in favor of White.

Prior to this round, Smyslov faces off with Keres in round 24. Keres, with white, launches a strong rook attack on Smyslov’s king side. Had he made a couple more supportive moves ( blocking the Balck King’s escape) he might have actually gotten the point. Smyslov sees through Keres’ rook sacrifice and passes on it to play a more accurate move that opens up the diagonal, the d-file, and strong points in the center. In the first half of the tournament, in round 9, Smyslov put Keres under cross fire in an inferior QGD.

His victory in Rounds 24 and 25 cinched the victory as he entered round 26 a full pont nad a half ahead of Reshevsky. By round 27 he maintains a 2 point lead only to shrink ny ½ point in one round by Bronstein in round 28. On October 23, 1953, he finished round 30 with 18 points in a clear 2 points ahead of Bronstein, Keres and Reshevsky.

Epilogue:

Following the Candidates match, he faced Botvinnik. After 24 games ending in a drawn match, Botvinnik retained his title. The next interzonal cycle had him seeded once again for the 1956 Candidates Match in Amsterdam. He won that match again with another shot at the World Champion. Assisted by trainers Vladimir Makogonov and Vladimir Simagin, Smyslov won by the score 12.5-9.5. The following year, Botvinnik exercised his right to a rematch, and won the title back with a final score of 12.5-10.5. Smyslov later said his health suffered during the return match, as he came down with pneumonia, but he also acknowledged that Botvinnik had prepared very thoroughly.[2]Over the course of the three World Championship matches, Smyslov had won 18 games to Botvinnik's 17 (with 34 draws), and yet he was only champion for a year.

Smyslov continued to play in other World Championship Qualifiers though he never ended up qualifying for another World Championship. Even at the age of 62, he played in the Candidates Final in 1982. He lost to Gary Kasparov who went on to defeat Karpov, the World Champion at that time.

End notes:

This concludes my biographical study on this historic series on the Zurich 1953 Candidates match. Right now I will park the Delorean and tune her up for my next journey. The time machine is being calibrated for the late 1970’s. Stay tuned to see where I land next.